Florence welcomes Anj Smith and her first Italian exhibition at the Museo Bardini. The British artist represents the complexity of phenomena with the stunning accuracy of a Still-Life painter, rejecting the empty rhetoric of our times.

She tells us about her far from conventional, magical childhood world. Bright, luminous, she reminds us of a fairy, an elegant Pre-Raphaelite female, gazing always beyond, into what she defines “vital opening of thought”. Each day before starting painting she practices meditation in her studio in Finsbury Park . It helps her decompress from the stress and to think more clearly.

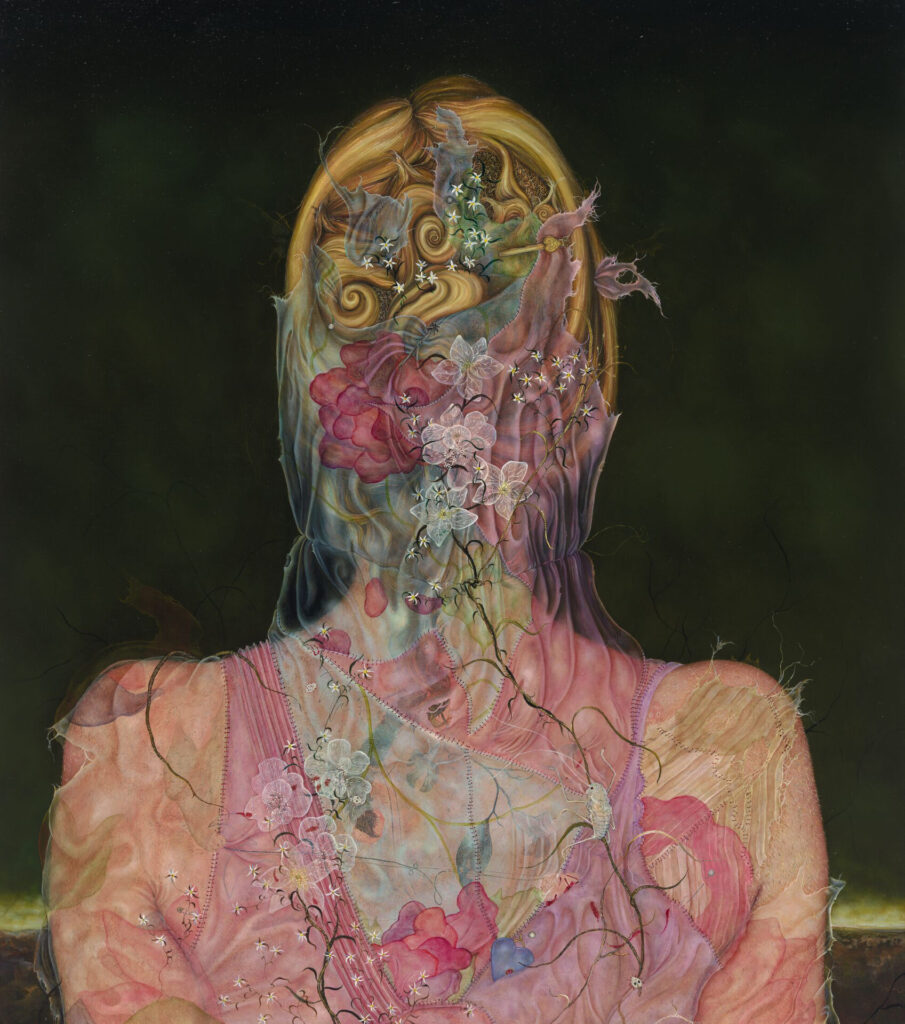

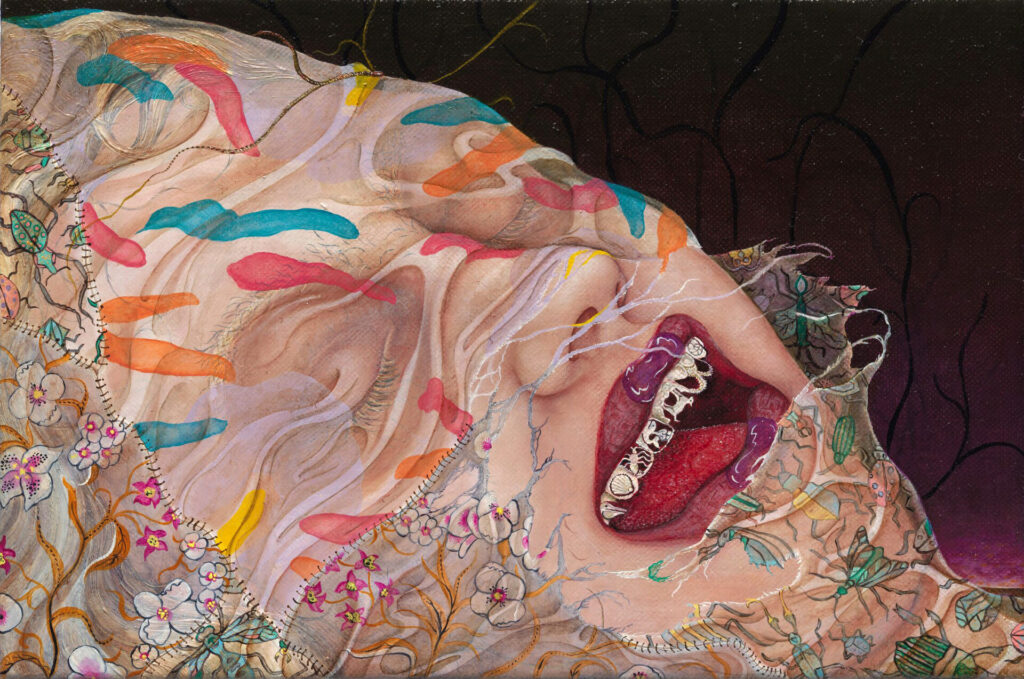

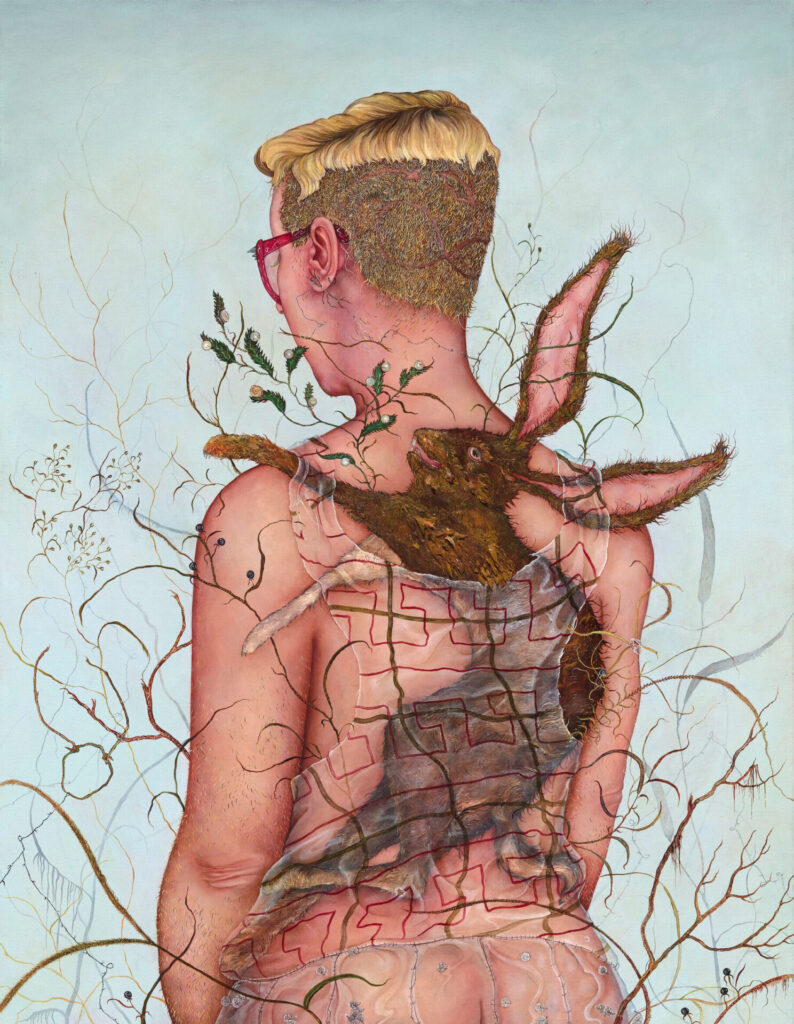

Anj Smith usually creates small format paintings, working meticulously with every piece and adding multiple miniature details (some parts have been painted with one-hair brushes). With strong references to art history, literature and autobiographical issues Anj Smith’s works are beautifully surreal, attractive, and hypnotizing.

Interview with Anj Smith

Your artworks can be compared to “Mirabilia”, microcosms embracing and preserving natural creatures, phantasmagorical figures, and symbolic objects. hey invite us to linger, to dwell on them, developing sensorial curiosity and space for thought. By letting ourselves be carried away, we discover we have renewed an authentic contact with Nature, and with our spiritual nakedness. Does your art propose to bring us back to the essence of the things? Is it an invitation to reflect, to slow down, as if it were an antidote for the complexity of he present?

You pose this beautifully. I’m not sure that it is possible to get to the ‘essence’ of things. Perhaps with painting, as with encounters with the natural world, it is possible to glimpse something ‘outside’ of logical thought or the reductive constraints that we are conditioned to operate from psychologically. However, the journey, or the attempt at one, is what these works seek to affirm.

Spending time in Florence amongst the treasures, always heightens my understanding of how rewarding and necessary these journeys are. Paintings draw me in, invite me to ask questions and often answer my questions with yet more questions. There is a vital opening out of thought. My own work carries a similar intention, offering a slowing down and the subsequent chance to revel in the mental space that creates.

Photo@2020 Alex Delfanne.

Literature has been a constant source of reference for you. Seneca wrote that “Nature created us for contemplation and action”. Your works of art are a source of wonder and fascination. Do you think they represent remains of a lost harmony or the destructive effects of a freezing aestheticism in our lives?

My four sisters and I grew up semi-rurally, creating magical childhood worlds unrestrained by parameters that an awareness of convention would have imposed. Some of the luminosity of those experiences I find I can still discover in literature – the transportation to another world and to other modes of thinking. I particularly love literature that plays with formal structure or subverts convention and genre, such as Giovanni Boccaccio’s masterpiece, ‘The Decameron’. This radical interrogation of formal concerns directly informs my painting, because the architecture of a book isn’t so different to that of a painting – I see a direct and helpful parallel.

It’s fascinating that you should bring up an idea of a ‘lost harmony’, because I have been thinking about that recently. Lucas Cranach’s ‘Adam and Eve’ is back on display at the newly reopened Courtauld in London and this painting is an old favourite for the way it interrogates exactly this kind of territory. However, I am more optimistic about human nature. I don’t think that all is lost or has been lost, it is just increasingly hard to access these places of wonder and discovery in our lives as we are constantly being conditioned to think in a small, unsatisfying way.

In an interview with The Independent (2017) Karen Wright describes your studio in Finsbury Park, the floor covered by splayed-open books, on the windowsill the collection of all the paintbrushes you have used, your table and your work clothes. Here your artworks are born. How does it all start and what is your relationship with the materials you use?

Before I start painting each day, I practice meditation. It really helps decompress from the stress and pressure of family life and enable the needed transition to think in a deeper register. Initially I started with this as a tool to combat anxiety, but soon found that after a few months, I could think more clearly and critically about my work, particularly in the mysterious depths that defy language of any kind.

Underpinning most of my work is a turning over of two basic but impossible questions – ‘what is there?’ and, if anything, ‘what is the nature of that thing? I have an exquisite castellated polyhedric prism, made of glass, on the writing desk in my studio. Aside from the incredible colours that it reveals in its refractions, even in the low London light, it’s principally there to remind me about the complexity of phenomena and to reject superficial explanations, labels, or rhetoric. My work is positioned in direct opposition to the easily consumable, shallow, constantly refreshing data feeds. We will lose our critical faculties is we embrace this as the norm, because we will become prey, vulnerable to seductive, empty rhetoric that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. It is bizarre that our need for content and critical awareness is now regarded as a radical demand by some. So, the importance of this cannot be overstated, within the worlds of painting and beyond.

«One of the amazing properties of Art is to encourage a much deeper perspective and to encourage contemplation and thought on a more complex level» (Anj Smith)

©Anj Smith, Landscape with Deep Void,2020. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo@2020 Alex Delfanne.

We are really grateful to Anj Smith for sharing her private memories, life, thoughts, and experience with us. Our sincere thanks to Hauser and Wirth for permission to reproduce images, to Sergio Risaliti Director of the Museo del Novecento and Costanza Savelloni Press office for having made possible this interview. Let us be thankful to our translator Tanya Di Rienzo for her competence in revising texts from Italian into English.